My books are impossible to read straight through. In fact, every time I have to proofread them before sending them off to the publisher, I fall asleep repeatedly. You really don't need to read my books to get the idea of what they're like; you just need to know the general concept.–Kenneth Goldsmith, "Being Boring"

Yet there it is: 800 pages, daring you to try it, taunting you with the right to say that you read an entire New York Times cover to cover, much as that original paper must’ve dared Kenneth Goldsmith to type it.

Of course, no one would ever be likely to conceive of reading an entire New York Times as a desirable accomplishment if Goldsmith hadn’t first transcribed it into literature. That’s why he’s the perfect, paradoxical poet laureate of this blog devoted to a life of semi-professional reading: On the one hand, the first poet of non-readers, one who invites that distracted state in which we all spend much of our days skimming over paperwork and blog feeds and status updates. On the other hand, a poet who commits his own time to reading differently, who looks at the texts that we churn out daily and recycle just as fast, and decides to spend years at a time converting those texts into doorstopping $30 paperbacks.

But can I actually read the thing? Should I, when the poet himself tells me not to? One thing I quickly learned upon looking into Goldsmith’s earlier book Soliloquy is that the above claim—that you “just need to know the general concept”—is not altogether true. It’s one thing to know the general concept of that book (that Goldsmith recorded and transcribed everything he said for a week); it’s another to experience the bizarre stops and starts of real speech, the mysterious one-sided conversations with Marjorie Perloff, the now-hilarious conversations about the cutting edge of the internet circa 1997. You may not need to read the whole thing, but reading at least a part of it reveals the innumerable surprises that crop up when you try to turn a concept—especially a deliberately fanciful one—into a realized practice. And if reading just a part of the poem makes a difference, maybe reading the whole thing, in all its patience-trying bulk, will add yet another layer of experience?

So far, Day is less full of surprises than Soliloquy (click those two, folks, if you want some generous samples of the books in question). After all, few of us have ever seen one human being’s unedited verbal output converted to print, but most of us have read a newspaper. Transformed into an 800 page modernist epic, made to stand toe-to-toe with Ulysses and The Making of Americans, the New York Times (surely the journalistic Hector to Joyce’s literary Achilles) comes out looking like nothing so much as a compendium of junk. Walls of temperatures and stock quotes, page after page hocking sales at Macy’s and absurdly-priced wristwatches, ad nauseam analysis of petty political TV spots—it may be difficult to get the news from poetry, but it seems even harder to get poetry from the news.

This, however, may be surprise #1 in itself: Right from its Capotean epigraph (“That’s not writing. That’s typing.”), Day presents itself as a postmodern critique of literary creativity. In practice, however, it may turn out to be a more old-fashionedly modernist critique of journalistic banality.

In any case, I’m not giving up yet. A real reader relishes a challenge, and the best way to get me to read anything is to tell me it's unreadable.

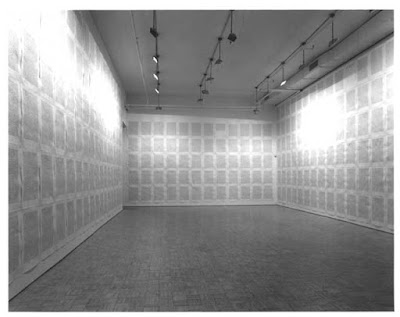

Soliloquy, in its first life as a gallery installation.